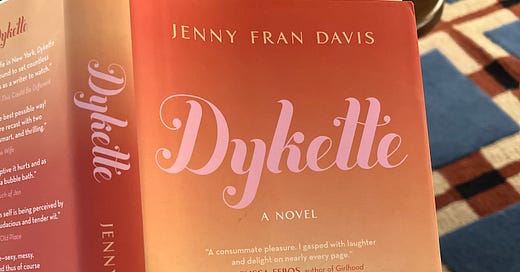

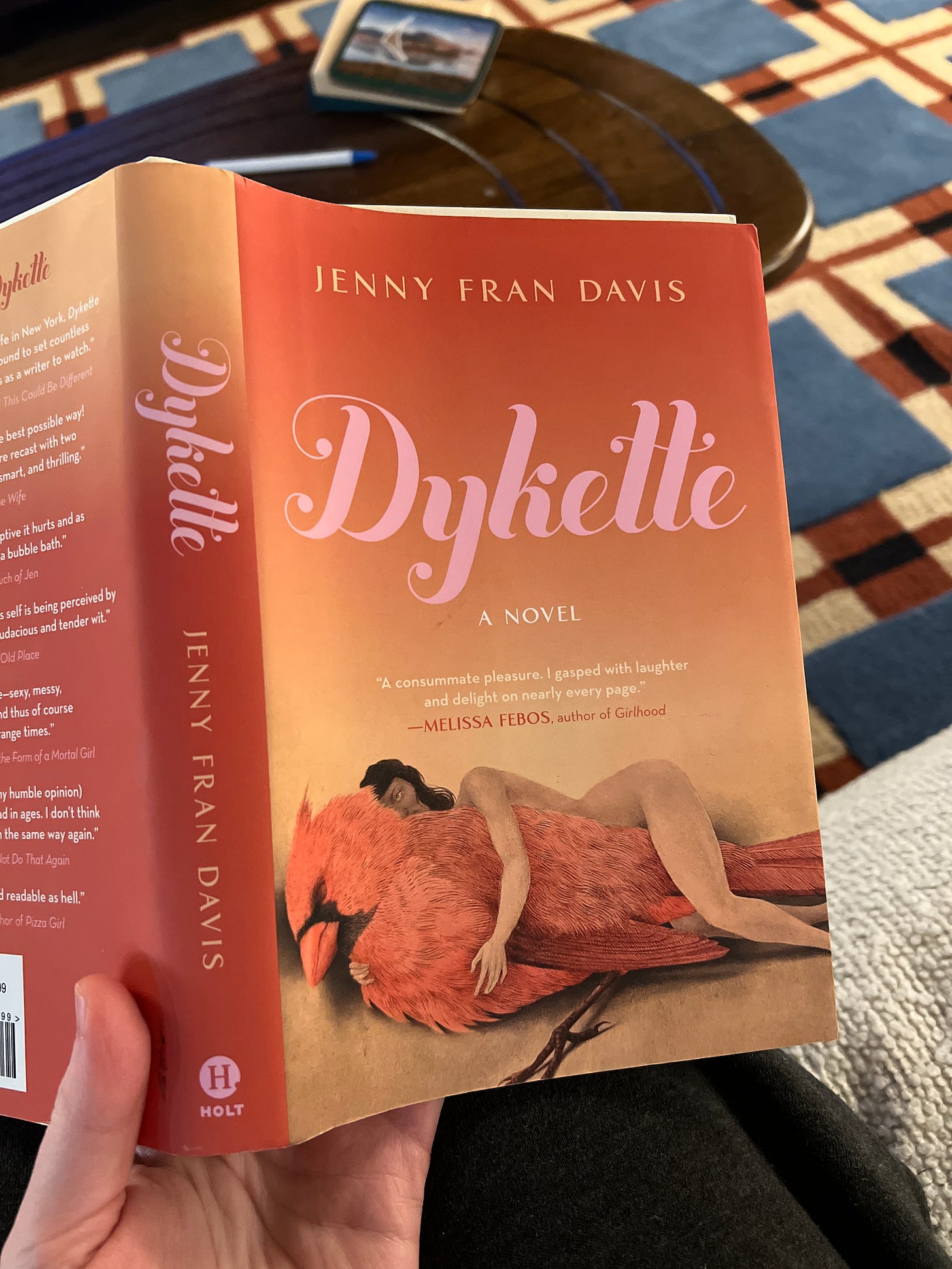

Last week, I was getting vegan tacos in Andersonville like I was inside of a joke about lesbians written in 1992. The cause célèbre was Dykette, the sizzling sophomore novel from Jenny Fran Davis and THE discourse-driving lesbian book of 2023. In the book, two scene-y mid-twenties lesbian couples spend Christmas at the upstate second home of a Rachel Maddow insert and her age-appropriate girlfriend. I found the story delightful in its cultural specificity and original in its exploration of intergenerational queer dynamics. But a lot of other queer readers hated it. When I mentioned this book to a lesbian bookseller, they physically grimaced and let out a low “oooooh,” like I’d just punched them in the gut.

For this review, I brought in the big guns. Kait is an esteemed Lesbian and a smart writer. We have been friends for 11 years and I love her more than life itself. Below is a wide-ranging interview on herstory, Dykes To Watch Out For, But I’m A Cheerleader, and living in post-feminist hell. If you enjoy, subscribe to Kait’s Substack: the wrong word. You can subscribe to Herstrionics with the green button :)

E: Hi Kait. Thanks for talking Dykette :)

I’m curious to hear what you thought this book did well. We talked a bit earlier about how the world the book creates felt so vivid and familiar—do you think this is a true novel of manners?

K: Hi Elaine. :)

The characters and social dynamics in this book will feel exceedingly familiar to anyone who was a lesbian in a certain type of social scene from ~2014-2019. It’s interesting to me that the book is set at the tail end of this period, which some might interpret as wanting to avoid the COVID issue. I actually think it’s more interesting, that the culture was really changing around that time and Dykette delves into the anxieties and social tensions that were pulling it apart. Of course, people like the characters in the novel still exist, but in my opinion lesbian culture has very much moved on from them.

So in that sense, it is a novel of manners, but in a kind of hyper-specific way. There’s limited engagement with how these women/couples/lesbians at large fit into mainstream society (or don’t). Even when they deal with classic novel-of-manners topics like marriage, it feels walled off from any real significance, like an imitation of the thing itself (which, ironically, was one of those cultural anxieties I mentioned earlier). The hyper-specific social scene the novel is interested in is neatly mirrored by the setting of a vacation home with no outside visitors other than the six characters, which I thought was clever.

E: I love that you brought up the specificity of the time frame and the cultural eruptions that were happening then. This book is a cornucopia of 2017 lesbian trends that would be unimaginable today (the winkingly trad butch/femme dynamics, Instagram as a watering hole for lesbian culture and art). Part of me reads that cultural moment as a transition from the normcore self-seriousness of the Obama era to the grungey, hedonistic androgyny of today. I’d love to know how you’d characterize those trends and what forces you think are behind them—the end of the marriage equality movement, the election of Trump, and COVID especially seem to me to be influential.

K: I honestly think the two of us could write a 1000-page anthropological study of 20teens lesbian trends—there was truly just so much going on at that moment.

Obviously the butch/femme dynamic is a huge part of this novel, maybe the biggest part. As we both remember, the “winkingly trad” thing was HUGE at that time. Crucially, though, many of us that engaged in it didn’t really know if we were serious about it or not, or if anyone else was serious about it, which I think JFD really captured. So much of lesbian culture is about the tension between sameness and difference (both between women and between us and straight people), and at that time it was really palpable. The end of the marriage equality movement probably had a lot to do with that. For a lot of gay people, especially those a little older than us, that was a real “what now?” moment. Like, now we can get married, but what does that mean? Does it mean anything?

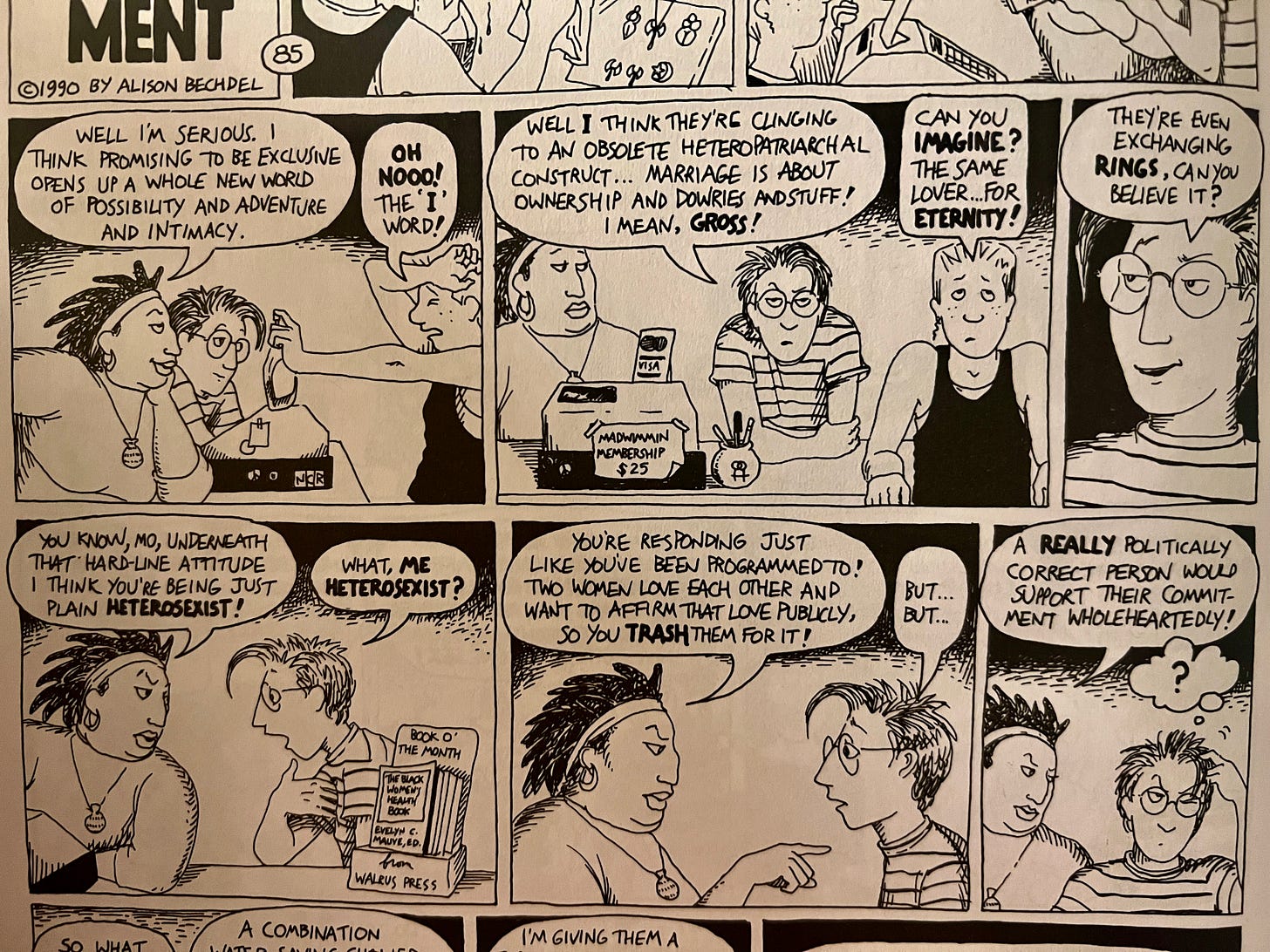

Before gay marriage was federally legal, there was a lot of debate about whether it was “subversive” or “assimilationist” to get married. I think at that time, you could argue either side and make some valid points (there are definitely some DTWOF [Dykes To Watch Out For] comics about this topic). As you’ve often said, to be gay is to be violently alienated from mainstream society, and I think those who wanted to get married could resolve the tension of imitating the thing that rejected them by seeing it as a subversion. In the later Obama years, though, especially post-Obergefell, this point of view became increasingly difficult to maintain, and the heightening of this tension caused a lot of people to behave in very strange ways. In earlier times, there was a lot to be gained by saying “we’re just like you.” Once we gained it, it became embarrassing to still feel that way—hence, the semi-ironic, “I’m-joking-unless-you’re-serious” engagement with marriage and butch/femme.

I’m a big believer in labels as descriptive and not prescriptive, so it’s also interesting to think about what identity labels mean to the characters in the novel (and how those meanings are historically specific). One of my favorite scenes in the book is when Sasha and Jesse are fighting and Jesse basically tells Sasha that she doesn’t get it because she isn’t gay. On its face, that’s ridiculous, because they’re in a lesbian relationship, but it’s also kind of true. What does Sasha mean when she says she’s a dyke? In a lot of ways, she hates other women and sees them as competition, which is a total perversion of what “dyke” means to me. These meanings change constantly, but that time period really felt transitional, like we weren’t sure what any of these words meant anymore. Sasha and Jesse’s ambivalence about their own relationship and where it’s going is a microcosm of this.

E: I like how you say “as you’ve often said,” as though I’m constantly going around telling straight people that they’re violently alienating me (when in reality I’m only doing that, like, 30% of the time). But I love that you brought up DTWOF, because not only is it foundational to both of our personalities, it also presents a challenge for us as Lesbian Cultural Analysts. DTWOF tracks lesbian life from the 1980s through early 00s. Many of the then-burgeoning trends it examines have also been up-and-coming on our scene. I’m thinking about things like polyamory and pronoun experimentation, both of which I started to notice right after the time period in which this book is set. We also know from feminist history that mainstream “acceptance” of queer people is cyclical and not linear. I guess I’m wondering whether lesbian culture is also cyclical—is anything really original, or are we just cycling in and out of the same trends depending on the political climate?

The other thing DTWOF brings up for me is the concept of lineage or, to be corny about it, Queer Elders. I think the book is critiquing something about the queer cultural value (or meme, depending on who you ask) of “honoring” older generations of lesbians. I’m not sure, though, whether the critique is that we shouldn’t bother with elders at all, or that the kinds of elders the book depicts (conventional and materially successful) are unworthy of our attention. What do you think?

K: Okay, wow. This really has me thinking about lesbian history and how we might periodize it. Obviously we just addressed the significance of Obergefell, but if we want to go back further I think the other really obvious before-and-after is AIDS and the related abandonment of the more second-wave feminist view of what it means to be a lesbian. In DTWOF, that shift is much fresher and so many of the comics deal explicitly with nostalgia for a feminist ethos that’s still dying out. By the time we get to Dykette, we’re deep into post-feminism and that culture feels completely dead and buried.

There is a LOT we could get into here but let’s start with the culture being cyclical vs linear issue. It’s both and neither. Trends like butch/femme and monogamy go in and out of style, but if we zoom out a little bit it really feels like we’ve just been floundering in a post-feminist hell since the 1980s.

That brings me to the Queer Elders issue, because these things are intimately linked. There’s a lot of false nostalgia in the queer community (especially among the politically-minded), and people tend to revere past generations without acknowledging our embarrassment at their shortcomings. The result of that is often a solemn admiration for elders in a general sense but a rejection of them on an individual level. I kind of just did that when I said we’re living in a post-feminist hell, because obviously the second wave also had serious issues and I don’t have a lot of respect for some of the women of that era with whom I disagree.

The generation gap in Dykette is interesting because it lays out this dynamic so clearly. I didn’t interpret it as a rejection of the older characters or casting them as unworthy of attention so much as highlighting the self-absorption of both generations. The younger women love the idea of a relationship with their elders, but they don’t respect them in reality. The older women feel that the younger generation should be impressed with their success and feel embarrassed when they aren’t, because they don’t understand what the younger women believe in (which, to be fair, they don’t understand themselves). All the women in the book fail to recognize and accept their own flaws and are therefore unable to recognize and accept each other as full, flawed people. That’s a value everyone loves to talk about, often with the language of “queer community”, but one that is almost never lived out in real life. It’s easy to venerate a person who doesn’t exist, but real people say cringe things and act imperfectly and often we treat these transgressions as unforgivable because they ruin the vibe of a utopian community with wise elders that we can all look up to. So for me, the takeaway is less about if we should bother with elders or not and more that maybe we should try to accept (or reject!) each other on a human level instead of viewing every queer person through a generalizing lens of identity (whether that identity is related to gender, sexuality, generation, or something else).

E: I think this is really borne out in the response to the book. It has 2.96 stars on Goodreads and a LOT of irate reviews. Interestingly, most reviewers take issue with the very thing we appreciated about the book: the familiarity of the material. So many people wrote iterations of, “I’ve met white femmes like Sasha and they’re the worst!” or “I know these pathologically toxic queers in real life.” It was interesting to me that queer readers acknowledged the honesty of the writing—no one is arguing that Sasha and the world she inhabits are over the top—but objected to the “unlikability” of the characters. I think this policing of queer culture is really interesting, especially in the post-marriage equality era where it feels like personal comfort, and not respectability, is the driving force behind it. It reminds me of an interview I read with the showrunner for Bridgerton about queer storylines. She said that it was important that a lesbian relationship on the show ended in a “happily ever after” and not a “queer trauma.” This astonished me because while the show’s whole schtick is being an Anti-Bigotry Fairytale, it has not shied away from depicting other forms of “trauma”, e.g., really regressive misogyny, child abuse, witnessing the death of a parent.

I guess on the one hand, I’m glad that media is moving away from depictions of queer people as one-dimensional villains or cautionary tales. But on the other hand, it almost feels like there’s no room for complex queer experiences and characters. I rewatched But I’m A Cheerleader at a pride party and all I could think was, this would be so canceled now. The thing that I love about that movie—its good-humored and relatable handling of conversion therapy and familial homophobia—feels like it would be too much for contemporary queer audiences. I guess I’m asking, do you think these critiques of the book are fair? We talked a bit earlier about how I see parallels between Dykette and Emma, a beloved book with a lead Austen famously called “a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.” Why do you think we care so much about queer characters being likable?

K: I love when a book is poorly reviewed in ways that prove its truthfulness. Why do people want likable queer characters? Because they see themselves as likable. People often don’t like to see their own flaws or the flaws of their culture laid out so explicitly, but that’s also kind of the point of art (especially a novel of manners). We all recognize the toxic queer as something outside of ourselves, the “bad” part of the culture and not a collection of trends and values that also act on us and inform our own behavior. Most of us are unlikable at times—we say and do ugly things and we have ugly feelings. As much as I dislike people like Sasha in real life, I felt that her character was very human. We see her vulnerability and her confusion and although she behaves badly, we can relate to her emotional turmoil and sympathize with her to some extent. Who hasn’t felt crazy in a bad relationship? Who hasn’t been 25 and not known what they want out of life? Anyone who pretends they’ve never thought or done something toxic in such an emotional state is lying to themself. That’s not to defend the character, because I don’t think she’s defensible. It’s just to say that she’s bad in a mundane kind of way that many of us are also bad at times.

That brings me back to your point about personal comfort replacing respectability, which I think is really insightful. In the pre-marriage equality years, the conversation was always about “good representation” and “stereotypes.” There were very clear lines between what was acceptable (anything that humanized gay people and portrayed them as similar to straight people was good). Promiscuity, drug use, and general immorality were viewed as deeply offensive. Tragedy was acceptable sometimes, but only if it was in the form of injustice. These standards served a political purpose, to market our humanity to the mainstream culture.

When we replace those standards with personal comfort, everything goes out the window. Such standards serve a psychological purpose rather than a political one, to protect the reader/viewer from any uncomfortable feelings. I think a lot of readers struggle to engage with “traumatic” narratives because they don’t want to engage with the ways in which experiencing trauma can make you weird or even toxic. This goes back to my earlier point, that we don’t like to be told so clearly the ways that we are unlikable. But I’m A Cheerleader is so great because it doesn’t shy away from this at all, but you’re so right that it would be so canceled now for that exact reason. There isn’t an explicit engagement with trauma in Dykette, but for me that’s an unspoken part of all queer literature, because of that violent alienation we discussed earlier. I think in some cases, we aren’t even able to acknowledge this trauma and the ways it has shaped who we are. Especially when those ways are bad.

One way this comes through in Sasha’s character is her clinginess and jealousy. She is dealing with a kind of classic lesbian problem: I’m out, I’m free, I don’t have to marry a man. So wtf am I supposed to do? That freedom can feel very scary and that’s why the horrible, drawn-out post-coming-out lesbian relationship is such a common trope. Sometimes we cling to a really normative relationship regardless of whether it’s good for us because it makes us feel safe and stable. It can be SO scary to feel like your life has no script to follow and you’re totally on your own. I think Sasha fixates on monogamy and marriage because of that—she needs a way to define herself and something to structure her life around. To which I can only say—many such cases.

E: The way I’m so chuffed that you called me insightful. One more question and then you’re off the clock: should lesbians (using “lesbian” in the non-prescriptive cultural sense) read this book?

K: Yes! I think it’s valuable in several ways. For old millennials/gen xers, it’s a great primer on the Instagram generation. For anyone who came out during COVID, it’s a good document of how in the trenches of insane nonsense we were back then (now we have a totally different kind of insane nonsense). And for those of us in the middle, it’s a good opportunity to reflect on the things we discussed in this review and how those have been present in our own lives.

I think my hope for this book is that we read it, we hate the characters, we think about why we hate the characters, and we collectively work out some of our intra-community issues. Not to devolve into memes but ladies, why are we competing when we should be kissing???? Or fighting for a better world. Or, ideally, both.